“This is surreal!” You hear that ever so often, when folks come across something unusual or something that’s outside the scope of their experience and expectation. The literal sense of the word, though, (and I’m quoting the dictionary here) is “strange, especially because of combination of items that are never found together in reality.” That sense is best presented in the visual arts, and, though digital means have made it possible for anyone with a febrile imagination to provide some such experience, nothing can be more awesome than the works of the Surrealist painters.

Not even the songs and music we called ‘psychedelic’ come close. But, since I like to add music to my posts, and since imaginative music and lyrics are the only ‘comparables’ I can think of at the moment, you’ll find some pieces, possibly totally incongruent, tossed into this post at random. Here’s one – a visualisation accompanying Edvard Grieg’s piece from Peer Gynt – In the Hall of the Mountain King:

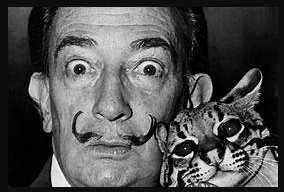

Coming to Surrealism – I’d always thought that Salvador Dali (1904-1989) was the ultimate Surrealist, not just in his work, but also in the way he looked.

But, now I’m not so sure.

He had a Grandaddy in the Netherlands.

At the time of writing I am in the Netherlands, in a small (in size, not in impact) city, of a hundred and forty two thousand resident souls. It’s called ‘s Hertogenbosch (the ‘s is not a typo). It’s what was once a fortified medieval town, chartered in the late 1100s, which outgrew its walls sometime in the late 1800s. The official name is, I learnt, the contraction of “des hertogen bosch”, old Dutch for ‘the duke’s forest’. While the name is not actually a mouthful (especially for my countrymen and me, for whom names sometimes comprise all the letters of the alphabet), the Dutch have an abbreviated version – Den Bosch.

So, does that ring some bells ? There’s Bosch (the German engineering giant), there’s Harry Bosch (Michael Connelly’s sombre protagonist), and there must be a host of other Boschs. When it comes to Surrealists (!!) however, there’s Hieronymus Bosch (1450-1516), the artist from Den Bosch. His is a case of a person so proud of his heritage that he replaced his surname with the name of his town! He was born Jheronimus Van Aken. (The Dutch pronounce the Je as Ye, and the Jhe as Hye, therefore the English, with their penchant for placing their stamp on every word they come across, gave us Hieronymus).

Grandad Van Aken, Dad Van Aken, and three of his four uncles Van Aken were painters, so young Hiero was born with pigments for blood, palettes for palms, and pencils and brushes for fingers. And, since violence (both social and political) and gleeful mayhem were the order of the day in the 1400s, often carried out in the name of what we now call the Catholic Church, (which had a firm hold on the Christians of the Western world of that time), he was born with confessional windows for eyes and Papal Commandments for a navigation system.

With these elements, rose the painter.

There being no better way to experience Bosch the Surrealist than to visit the Jheronimus Bosch Art Centre at Den Bosch, that’s what we decided to do.

Using (what else?) Google Maps (!) we made our way to the area, just inside the old fortress walls, and walked to the pinpointed location, where we found a imposing and very impressive …. church (?!).

It didn’t correspond to our idea of an art museum, so, tearing our eyes away from Google Maps, we looked at the sign boards around which assured us that we were, in fact, at the Jheronimus Bosch Art Centre!

Music break! Here’s Duelling Banjos, the terrific piece that was featured in the 1972 film ‘Deliverance’:

Let’s continue.

So, in we went, and…. WOW ! It is something truly spectacular. The building and its appurtenances, the lighting and the viewing devices, and of course, the staff, are in the realm of reality, but the art exhibited, whether in paintings, sculpture, reproductions or collages, is truly surreal, in the dictionary sense of the word (see above). And the exhibited art (of and related to Bosch) is not the only impressive art to be seen. The church building itself is an imposing architectural work, with a breathtaking interior, and walls, ceilings and stained glass windows replete with beautiful pictorial representations from the Bible. There is also a huge wind organ, which, we learnt, is still performed on, a few times a year. This is a Saint James Church, a Catholic church built in 1907 on the site of an earlier (1805) church that had been demolished following a fire. While this building has ceased to be house of worship (in 2002), it has remained a national monument. The Jheronimus Bosch Art Centre was opened here in 2007.

It may seem irreverent, housing a retrospective of, and a tribute to, a Surrealist, in what was clearly intended to be a Catholic house of worship. However, thinking back on our experience, it does make a certain sense, to me.

And since I brought up the word ‘irreverent’, here’s the famously irreverent Frank Zappa with Muffin Man:

Back to the art.

The problem in describing something truly surreal is that it is indescribable, since the vocabulary of any language is capable of encompassing only everything that constitutes life or the situations that life presents us with. (‘life’ as we know it!). There are really no words for the inconceivable. And so it is for the unbelievable art around in that museum, in the form of Bosch’s paintings and the figures (3D representations of beings from Bosch’s paintings) that are suspended in midair. It is like entering what we would now call a virtual world (though not a digitally created one).

Here are a few pictures of Bosch’s work.

And here are a few pictures of 3D versions of creatures/characters from his paintings

And now, let’s try Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds, from (who else?) The Beatles ! :

And so, back to Bosch.

The first thought when one views the creatures in Bosch’s paintings is that he probably lived on a diet of magic mushrooms (and perhaps that’s all it really was! Which would mean any effort one makes at interpretation is just one’s own attempt to find justification, like hanging on to a pillar when in a tornado). But looked at really closely, each work seems to correspond to the themes of ‘good’ that leads to reward, comfort and heaven, and ‘bad’ that leads to suffering, destruction and hell. While almost all of Bosch’s creatures are grotesque chimeras, they seem to be identifiably either benign or malign in their ‘actions’. And most of his works (including his famed triptychs) present composites of three distinct realms – this world, heaven, and hell.

Even with this interpretation, one may think that Bosch’s artistic imagination would require extreme stimulation to even visualise the kind of anatomies and actions that he presented in his paintings. But then, one realises that he lived in the 15th century, when, publicly and in broad daylight, humans cheerfully visited on captives (whether they were fellow humans or other living creatures, and whether for punishment or for sport,) the kinds of horrors and atrocities we would describe as ‘unspeakable’ today. (I’m staying away from presenting examples since this piece is intended for readers of all ages and sensibilities.)

So, what was Bosch trying to do? Merely entertain? Titillate ? Amaze? Shock? Cause wonder and awe? Stretch people’s imagination? Tell people there are other worlds out there?

My take is that, perhaps, in presenting inconceivable extremes, he was doing something that a few writers, poets and painters, through the ages, have attempted (in vain) to do, that is, slap their readers, audience and viewers in the face with the extremes in human and social behaviour, and, cause them, through such catharsis, to reflect on the need for restraint, moderation, and balance.

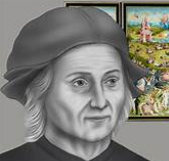

Here’s someone’s depiction of Bosch, indicating, with that devil in the water, his capacity to see more than other folks could.

Maybe I’m reading too much into all this. Even if so, one thing’s for sure – for me, Surrealist painting will no longer be just a style of painting. Each work will be something to ponder over and to interpret in a manner that would help me clarify my view of our world and the role of our species in it.

To end with, here’s Jan Hammer with Day 5 – The Animals, from his 1975 album The First Seven Days. There isn’t a video, but you could unleash your imagination !

Now, dear Sir, that was a surreal reading experience!

Jan Hammer sure has a surreal guitar!